Before us, we have two outstanding frescos, Masaccio’s The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden, circa 1424-1427, commissioned by the Brancacci family for their private family chapel in Florence. Here, as in other works of art from the Early Renaissance period, we see art produced for private purposes by the elite or nobility of the era.

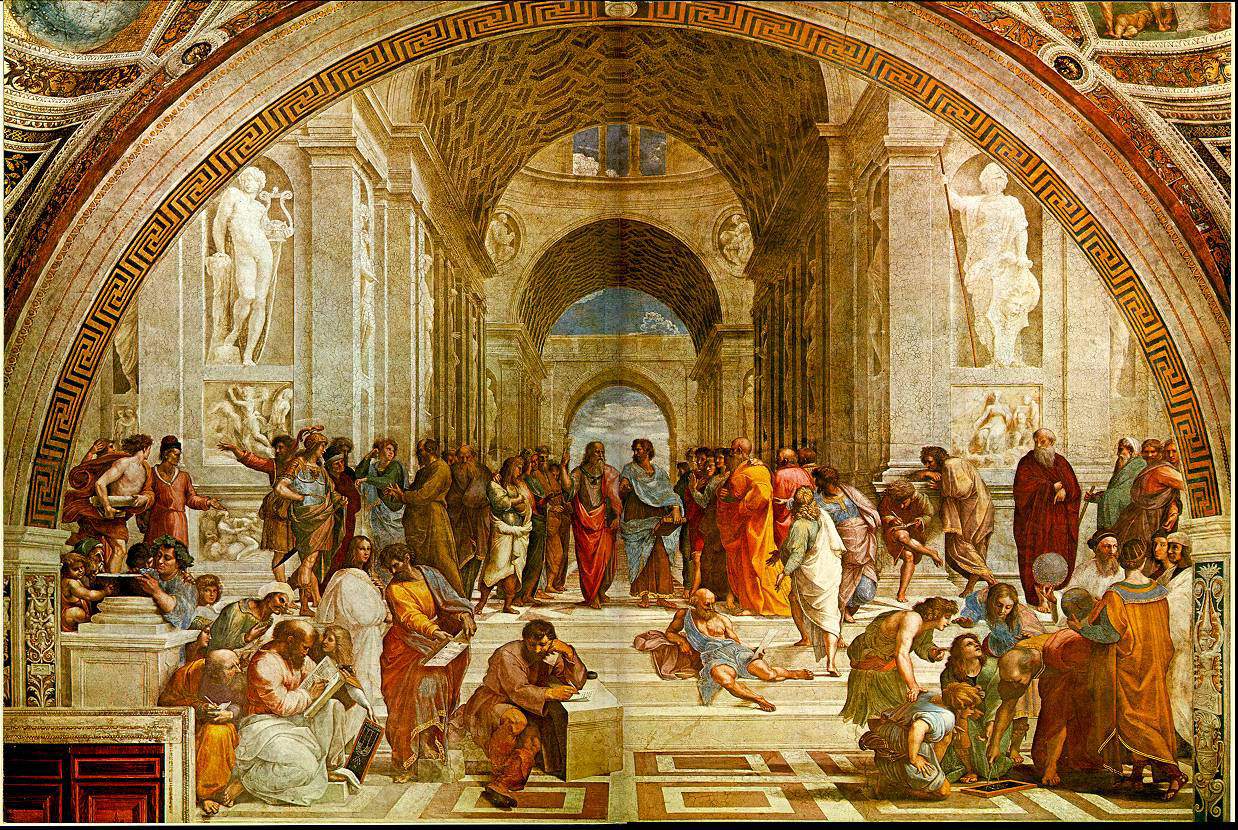

Before us, we have two outstanding frescos, Masaccio’s The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden, circa 1424-1427, commissioned by the Brancacci family for their private family chapel in Florence. Here, as in other works of art from the Early Renaissance period, we see art produced for private purposes by the elite or nobility of the era.The other fresco is Raphael’s The School of Athens painted between 1509-1511 for Pope Julius II’s Stanza della Signatura in the papal apartments in Rome. This High Renaissance fresco is an example of the patronage of the masters now being taken over by the Popes, and the Renaissance capital’s change in location from Florence to Rome.

Unlike 14th Century Italian and 15th Century Northern European art, Masaccio’s work is peppered with innovations that until this time had not been employed by others. He worked light with vigor and sharpness. In this piece, he uses a sharply slanted outside source to throw his images into deep relief and accentuate the forms. He’s balanced dark and light; using light as a unifying agent. Implied lines given to us by the shadows and tonal changes derive the figures’ forms. Unlike the stylized paintings of the past, Raphael’s figures are rooted to the earth by deeply, dark thrown shadows.

His narrative is biblical in nature as were many from this artistic period, but his narrative begins to show us a glimpse of humanism. Frankly, it’s not pretty. In fact, it’s borderline grotesque. He tells us their plight is heavy and everlasting by the starkness of the background and the structural accuracy of his figures. They’re heavy, full-bodied; not idealized images of antiquity. Adam and Eve are flawed individuals, crude and imperfect. Their pain is ever present.

In the coming decades, we’ll see more integration of humanism and classical elements.

The Transition to the High Renaissance

There are several trailblazers, which exemplify the qualities of the Expulsion, and the subsequent progression that led to Raphael’s masterpiece; for example, Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus.

While in Florence and employed by the Medici, Boticelli resurrected the neo-Platonic nude. A departure from Masaccio’s nudes, Venus is perfect, idealized, what every woman should look like. A pupil of Fra Filippo Lippi (who used his own beautiful mistress and children as models for his Madonna and Child with Angels), Boticelli represented Venus in a surprisingly worldly manner. His use of light was dissimilar to that of Masaccio, it is within the image, not without, and yet with it he emphasized the contours of his figures’ as did Masaccio. This balance of light and dark permitted him to suggest movement through flying and swirling draperies, ala Greco-Roman drapery stylization. Departing from Masaccio’s fall from grace depiction, Boticelli invites us to enjoy this secular, elegant, and romantic representation. She’s not to be hidden away or feared, but to be viewed as God’s perfection.

Another artist who contributed to the transition from Early to High Renaissance is Luca Signorelli, and his Damned Cast into Hell. Tapped by Pope Sixtus, Signorelli, like Pollaiuolo before him, showed great talent in depiction of muscular bodies, a variety of poses and foreshortening. Certainly, this piece of artwork influenced Raphael’s figure compositions. Up until this point, we had not seen many works of art depict the mass of form and arrangement of many figures. Here the lighting is omnipresent. There is no real source; a departure from Masaccio’s sharply directed lighting.

Now in Rome, also employed by Pope Sixtus, Perugino’s Christ Delivering the Keys of the Kingdom to Saint Peter, charges headlong into classical representation. Perugino employs perspective and converging lines as invented by Brunelleschi. The figures occupy the apron of a great stage space that extends into the distance to a point of convergence in the doorway of a central-plan temple. He reaches into antiquity and incorporates triumphal arches (modeled on the Arch of Constantine in Rome), flowing robs and billowing fabrics. As we’ll see in the School of Athens, he develops figures in both the foreground and background. Also seen in the School of Athens, Perugino and Raphael integrated two- and three-dimension space. The placement of their central actors emphasizes the axial center. Both artists organized the action systemically by using spatial science. These innovations of placement and mathematical expression had not been available in Masaccio’s time.

Into the High Renaissance We Go

With the School of Athens, Raphael summed up the Renaissance. Unlike Masaccio’s early Renaissance Expulsion, with its flatness and abstract composition, Raphael continued to build upon what Brunelleschi had started by employing perspective to perfection. Although the figures are cloaked, we see idealized anatomy, uniformity, resourceful foreshortening, and a reflection of classical cultures. The School of Athens, the Philosophy mural, includes a congregation of great philosophers and scientists of the ancient world, all revered by Renaissance humanists. Like Fra Filippo Lippi, he inserted himself and his contemporaries into this image; a unique and self-directed touch. He also paid homage to Plato and Aristotle, given them center stage.

Unlike the Brancacci family, but like the Medici’s before him, Julius expanded the application of art because he understood what could be accomplished politically, religiously, and civilly through the creation of art. Therefore, Pope Julius II began decorating the interior of the papal dwellings. Like the nobility and popes before him, he strove for authority through his art patronage. The School of Athens, part of a four-wall execution including Theology, Law/Justice, Poetry and Philosophy, represents the four branches of human knowledge and wisdom, which signified virtues and learning appropriate for the Pope. By commissioning such a mural, the Pope help raised the visual arts to the status formerly held only by poetry.

Raphael’s setting is a vast Greco-Roman styled hall with massive vaults, colossal statues of Apollo and Athena, pilasters, and ornate carvings; whereas Masaccio’s Adam and Eve are nowhere. Other than a glimpse of architecture, they are set upon a cold, non-descript abstract background. Raphael has embraced the classical interior with great exactness and passion. Vast perspectival space on two-dimensional surface equals the union of math and pictorial science. Masaccio’s lack of perspective leaves us with flat figures--their only definition given by Masaccio’s external light source.

Masaccio’s narrative is biblical; heaven and hell, fire and brimstone—you sin, you lose. Not so, for Raphael, he brings the secular narration to an honored level. He says there is more to life than religion. His Plato and Aristotle are central figures surrounded by ancient philosophers, scientists, and mathematicians—all embraced by the humanist movement. Massacio’s Adam and Eve, save a single angel, are alone—alone in their sin. There is no sin in Raphael’s collection of figures. His fresco vibrates with self assured and natural dignity, natural and calm reason, movement, ease and clarity, eloquent poses and gestures. His characters are engaged; except the brooding Michelangelo (perhaps a tongue-in-cheek depiction), and he carefully considered relating individual and groups to one another.

We see great advancements in techniques and innovations from the Early to the High Renaissance. For example, light gains directional qualities; gone are the glowing figures with a single light source for each. We see external light manipulated and then finally full employment of light with well-developed shadows and tonal differences. Linear perspective replaces flat, abstractness and artists begin to utilize both the foreground and backgrounds of their paintings—leading to more use of foreshortening. Although many works still maintain a biblical narrative, due to patron control, in the High Renaissance artists employ more humanism in their compositions. This leads to more artists breaking free from long-held doctrine, and taking control, which introduces the notion of artistic license and artistic freedom.

No comments:

Post a Comment